|

-

17th January 2017, 01:15

#1

Retired Member

New discoveries at the desert castle of Khirbet al-Mafjar

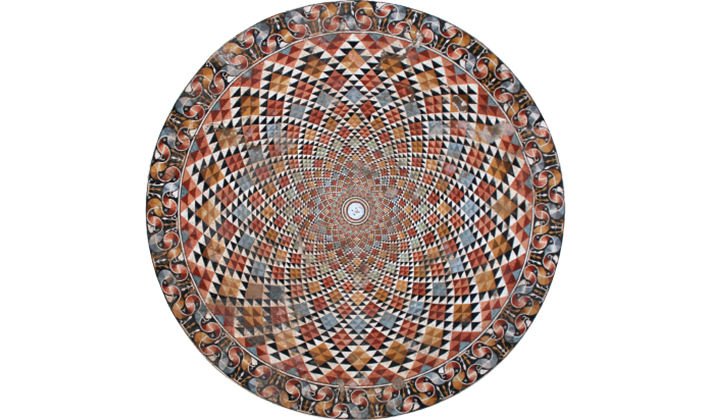

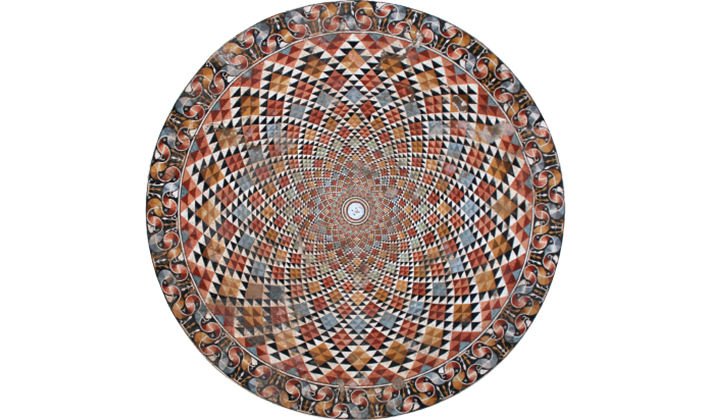

The palace’s bathhouse boasts a carpet-like mosaic floor measuring more than 16,000 square feet,

with five circles such as this one, all made from naturally colored stone tesserae.

In 1935, Dmitri Baramki, a young archaeologist working for the British administration in his native Palestine, began excavating three dirt mounds outside the ancient city of Jericho 25 miles east of Jerusalem. Baramki was concerned that important evidence of a Byzantine church or monastery inside the mounds was being destroyed by the locals’ habit of pilfering and reusing the ancient stones for building material. However, he soon realized that what he had found was not a Christian religious building at all, but instead, the remains of an eighth-century Islamic palace.

Though much of the palace complex was in shambles, likely destroyed by an earthquake in A.D. 747, Baramki’s team nevertheless unearthed detailed mosaics and stuccowork of the highest quality that once had decorated the palace’s walls and floors. Baramki also discovered a white marble ostracon inscribed in ink in Arabic reading “Hisham, commander of the faithful.” The phrase is probably the opening of a letter, and is the only writing found at the site. Local residents, who had previously called the mounds Khirbet al-Mafjar, “Ruins of Flowing Water,” for their location near an aqueduct, began referring to them as “Hisham’s Palace.” Soon archaeologists concluded that the palace had been built during the reign of Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik, the tenth Umayyad caliph (r. A.D. 724-743), Islam’s chief religious and political leader.

The Umayyads were a merchant family from Syria who converted to Islam in 627. Islam’s founder, Muhammad, died in 632 without leaving a clear system of succession, ushering in a period of strife. By 661 the Umayyads had ascended to the caliphate, having won the first of many wars fought for leadership of the religion and its growing sphere of influence. The first Umayyad caliph, Muawiyah ibn Abi Sufyan, moved the caliphate’s capital from Medina, in what is now Saudi Arabia, to Damascus, in modern-day Syria, where the family already had high standing, thereby boosting the power and legitimacy of the new leader. For 89 years the Umayyads reigned over an empire stretching from India to Spain. Their fragile hold on power was constantly threatened by various groups claiming rights to the caliphate, and they ultimately lost several key military battles to the Abbasid Dynasty, who finally wrested away control in 750.

Robert W. Hamilton was the head of the British Mandate for Palestine’s Department of Antiquities who oversaw Baramki’s excavations at Khirbet al-Mafjar and eventually joined him at the dig in the later 1940s. The sumptuous nature of the palace, much more extensively decorated than other Umayyad desert compounds found across the Middle East, could, thought Hamilton, only be fully explained by linking it to one particular short-lived caliph—a nephew of Hisham named Walid ibn Yazid, known from later Islamic writers for his love of music, wine, and women. “It existed for reasons which must be sought not in the realm of public affairs but in that of personal pleasure,” Hamilton wrote in his 1959 book, Khirbat al-Mafjar: An Arabian Mansion in the Jordan Valley. In another book, Walid and His Friends, Hamilton relates a story from the tenth-century text of Islamic historian Abu al-Faraj al-Isfahani about Walid bathing in a tub of wine, and then emerging intoxicated with the level of wine in the tub significantly lowered. Al-Isfahani does not mention where this episode took place, but Hamilton writes that it occurred in the palace’s bathhouse.

Remains of the Umayyad Caliphate’s sprawling 8th-century A.D. palace complex

at Khirbet al-Mafjar still stand near the city of Jericho.

Hamilton determined that Khirbet al-Mafjar was abandoned after Walid was killed in 744—allegedly assassinated by a family member for his wild behavior. “Walid and all his company, his singers, his horses and hounds, his builders and his girls were totally forgotten,” Hamilton writes. “Only the name of ‘al Mafjar,’ meaning ‘where water gushes out,’ or, by a quirk of language, less agreeably ‘the place of fujur (debauchery)’ may still be whispering to their ghosts of ancient pleasures dimly remembered.” With Baramki’s publications not well known, and the reports from the only other excavation of the site by a team of Jordanians in the 1960s lost, Hamilton’s emerged as the dominant narrative of the site.

Scholars today are quick to point out Hamilton’s colonial motivations, saying he, like many Europeans at the time, viewed Islamic culture as a mix of the backward and the exotic. Aside from a few late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century explorers, European powers had only entered the Middle East recently, at the end of World War I, establishing colonial mandates that lasted through World War II in what are now Syria, Lebanon, Israel, and other countries. The same scholars also note that the Islamic historians Hamilton relies on are widely viewed as biased against the Umayyads because they were writing under the Abbasid Caliphate, and had an interest in portraying its predecessors as corrupt and impious in order to promote Abbasid legitimacy. “Hamilton’s writings have cast this particular monument in a very superficial role in Islamic architecture,” says Donald Whitcomb, a University of Chicago archaeologist who, along with the Palestinian Authority’s Department of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage, is now leading the Jericho Mafjar Project. “I don’t deny that the Umayyads had some good parties, but I don’t think it was the purpose of the site.”

Now, thanks to Whitcomb and his team’s work, the story of Khirbet al-Mafjar is becoming one of nearly 400 years of long-lasting cultural, economic, and political achievement, rather than a few years of a wayward caliph’s escapades. And instead of casting the palace as an anomaly, this new understanding offers insights into the early development of Islamic cities, how the Umayyads sought to exert control and influence over an area mainly inhabited by Christians and nomadic Bedouins, and the persistence of culture even under shifting political, economic, and religious circumstances.

During Baramki’s and Hamilton’s original excavations, which covered more than 3.5 acres, they unearthed the remains of an impressive complex composed of a palace, bathhouse, courtyard, and mosque, all surrounded by defensive walls. The palace’s interior walls and ceilings are covered in extravagantly carved stucco in whimsical patterns, along with human and animal figures. Much of the imagery is derived from both the Greek and pre-Islamic Persian Sasanian Empires. Brick vaulting echoes building techniques from ancient Iraq. The floor plan of the palace, consisting of rooms arranged around a central courtyard, is reminiscent of those of the Romans. “There is no doubt there is something about this architecture that is an inheritance from pre-Islamic tradition,” says Katia Cytryn-Silverman, a Hebrew University of Jerusalem expert in Islamic archaeology.

The Umayyads not only esteemed the beauty of the imagery of their predecessors, explains Cytryn-Silverman, they were also employing styles associated with these powerful empires of the past in order to affirm their own present authority. “This was a time when pre-Islamic tradition was followed and admired,” Cytryn-Silverman says. “In this melting pot of past and present empires, the Umayyads were still looking for their language of expression and ways to demonstrate their rulership.

Source: http://www.archaeology.org/issues/23...-desert-castle

peace...

peace...

-

The Following 8 Users Say Thank You to skywizard For This Useful Post:

Aragorn (17th January 2017), Dreamtimer (17th January 2017), Elen (17th January 2017), Greenbarry (17th January 2017), Juniper (17th January 2017), modwiz (17th January 2017), RealityCreation (17th January 2017), sandy (17th January 2017)

Posting Permissions

Posting Permissions

- You may not post new threads

- You may not post replies

- You may not post attachments

- You may not edit your posts

-

Forum Rules

peace...

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Bookmarks